The Artist, The Nude Female and The Audience

The significant role that the audience plays in turning a naked woman into a nude artwork

In John Berger’s Ways of Seeing from 1972, he states ‘To be naked is to be oneself. To be nude is to be seen naked by others and yet not recognised for oneself. A naked body has to be seen as an object to become a nude.’ Berger posits this idea of the naked and the nude whilst also discussing the male gaze and the involvement of the viewer or the audience in turning a painting or an image of a naked person into nude art. In this case, and in most cases in art history, one discusses a female nude and a male surveyor. The idea of the naked suggests the unclothed figure is not posing or performing for the viewer but is simply doing the day-to-day tasks that would require being naked such as showering, bathing or dressing and undressing, something one would not normally do with the presence of an audience. Whereas, the motive of the nude has a more sophisticated undertone. When you think of a nude you may think of great art, of antique sculptures of nude Gods and Goddesses, or of classic nude paintings. The term naked is rarely used in this context and this suggests that naked is a more uncomfortable or uninteresting state. The naked is a natural state, the undressed figure is not disguised, posing, staged or performing anything other than themself. The nude, however, is art, a performance, it is what one perceives that the audience wants and enjoys seeing, not necessarily what is true. The nude can be altered and manipulated to one's desires, it is produced by society for the public.

The audience plays a predominant role in this discourse, simply because you cannot have a nude without a surveyor. The Toilet of Venus by Diego Velazquez, 1647 (Fig. 1), is a classic example of a female nude artwork. The figure of Venus is reclining on draped red cloth, with her back facing the viewer. You can see her face in the reflection of a mirror being held up by her son, Cupid. Venus is not directly engaging with the audience, she is presenting her body before presenting herself. Berger discusses this idea when he says ‘The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object - and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.’ By having the figure pose, facing away from the viewer, the artist is ultimately stripping her of her identity, or in this case, constructing a secondary viewpoint (Venus’ face in the mirror), therefore presenting her as an object to be viewed by an audience and nothing more. The idea of the mirror in this painting and the figure of Venus watching herself being viewed is alluded to when Berger says ‘Men act and women appear. Men look at women, women watch themselves being looked at.’ Venus is gazing out to the viewer through the mirror, watching the viewer gaze upon her nude body. In this painting, the artist and the model invite the audience in with a two-way gaze.

This idea of a multiple-gaze perspective is present and enhanced in Helmut Newton’s photograph Self Portrait with Wife and Models from 1981 (Fig. 2). The main focus of this photograph is a posed female model, she is nude in front of a large mirror wearing only a pair of stiletto shoes. She is positioned with her right hand on her waist and left hand resting on the back of her head, her body is fully extended, accentuating and enhancing her figure; mimicking classic pin-up model poses, not unlike a quintessential Marilyn Monroe photoshoot by Michael Ochs from 1955 (Fig. 3). As well as seeing the model in the mirror we also see the model from the back, this view of her body is cropped and much closer to the audience. To the model’s right, and behind her we also see in the mirror Newton himself in the process of taking the photograph. Newton is hunched over the camera looking through the lens in a long, oversized trench coat capturing the nude model in the mirror. Newton’s wife, June Newton, is seated beside the mirror opposite Newton and the models, with her leg crossed over the other, leaning her chin on her left hand, observing the scene with a possibly disapproving expression. The fourth person in this photograph is another female model who is seen to the left of the central model. All the viewer can see of this anonymous woman are her legs in the mirror, she is wearing a pair of high stiletto shoes, like the central figure. Victor Burgin points out an interesting contrast between the two models in his essay Perverse Space, he suggests that the second model is naked rather than nude as she is wearing shoes. The viewer cannot see above her knees so one should not assume she is fully naked. However, this photograph as a whole is clearly an archetypal example of the nude. The main focus is the fully nude model who is posed unnaturally in a way that shows off her body, she is in a studio setting and she has multiple surveyors; Newton, his wife, the other model and the public. The viewer has a significant role in regards to this photograph, the composition is not a traditional set-up, as the viewer is in the space with the models and this, in turn, invites the audience into the setting; the audience is exposed in the mirror just as much as Newton is exposed. The artist and viewer have infringed on the model's space, whereas traditionally the viewer and photographer would be in June Newton’s space. The surveyor and the surveyed become one in this photograph.

In the discourse on the naked and the nude, the audience has a larger role than the artist themself. Edgar Degas, for example, with his series of Bathers, such as After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself, 1890-5 (Fig. 4), portrays women doing what is normally a solitary, mundane task of bathing or drying themselves. By drawing these women nude and the treatment of very soft surfaces in pastel crayons, Degas has beautified this everyday act and created seemingly innocent observations of a private moment caught in time. Still, they are ultimately transformed into sensual beings with the introduction of the audience, who are watching a woman performing what is generally a private, non-sensual task. The female subjects in Degas's work do not face the audience, they are posed as if they are unaware of the presence of others. Once an unclothed woman’s normal, everyday function has been staged for a drawing or painting, the subject is no longer just naked, she is now a nude and this is due to the role of the perception of the public and the viewing audience who gaze upon her as a posed nude. The artist may have had no intention of creating a sexual image of a naked woman in their art, but that does not deny the transition from naked to nude once an audience of one or many is present. Once the artwork is visible to the public the artist and the model are no longer in control of how the work is perceived or viewed, therefore whoever views this artwork of a naked woman can ultimately turn the work into a female nude. This discourse is solely dependent on the presence of the viewer and the absence or backgrounding of the artist.

Where this discourse becomes slightly indistinct is when the artist themself becomes the model. In Tracey Emin’s self-portraits, for example, she sketches herself intentionally as a naked woman. Emin’s intent is to take control of her personal sexuality and assert her own identity. Sex 1 25-11-07 Sydney, 2007 (Fig. 5) is from a series of nude self-portrait drawings. These quick and fluid line drawings in blue watercolour depict an isolated nude woman (Emin). In Fig. 5 Emin is reclining, a classic nude stance, drawn slightly diagonal in the middle of a blank sheet of white paper. The figure has no face, her legs are bent, the form detail is minimal, and there are only suggestions of her arms, breasts and pubic area. Although this is a self-portrait it is not initially obvious that it is Emin, so her nude sketches do not necessarily expose her identity immediately to the audience. Emin portrays herself in quite a vulnerable position, not a beautification of the female form but more sexually explicit, which expresses her sexuality and her feelings about her personal sexual relationships. Nude art and self-portraiture are already vulnerable genres of art and this concept is elevated in Emin’s nudes. However, self-portraiture is a constructed view of the artist. The artist chooses what to show and what to conceal, within a frame, a still image. Emin is purposefully portraying herself as nude, the difference between Emin’s work compared to the previous nude works discussed is she is both artist and model, she is in control of the vulnerable position of nudity rather than someone else placing her or projecting her nude image for themselves or for that of the viewer. In The Nakeds, Gemma Blackshaw questions whether being in control of your image, your body and sexuality in your art really is empowering. Blackshaw’s discussion links back to the idea that once a work of art becomes public, the artist loses their control and the meaning and intention of the work become entirely up for viewer interpretation. So although Emin is initially in control of what she is presenting as the subject and the artist, and is fully aware that this is an element of the power of her work, the viewer ultimately still has a dominant role once the work is in the public view.

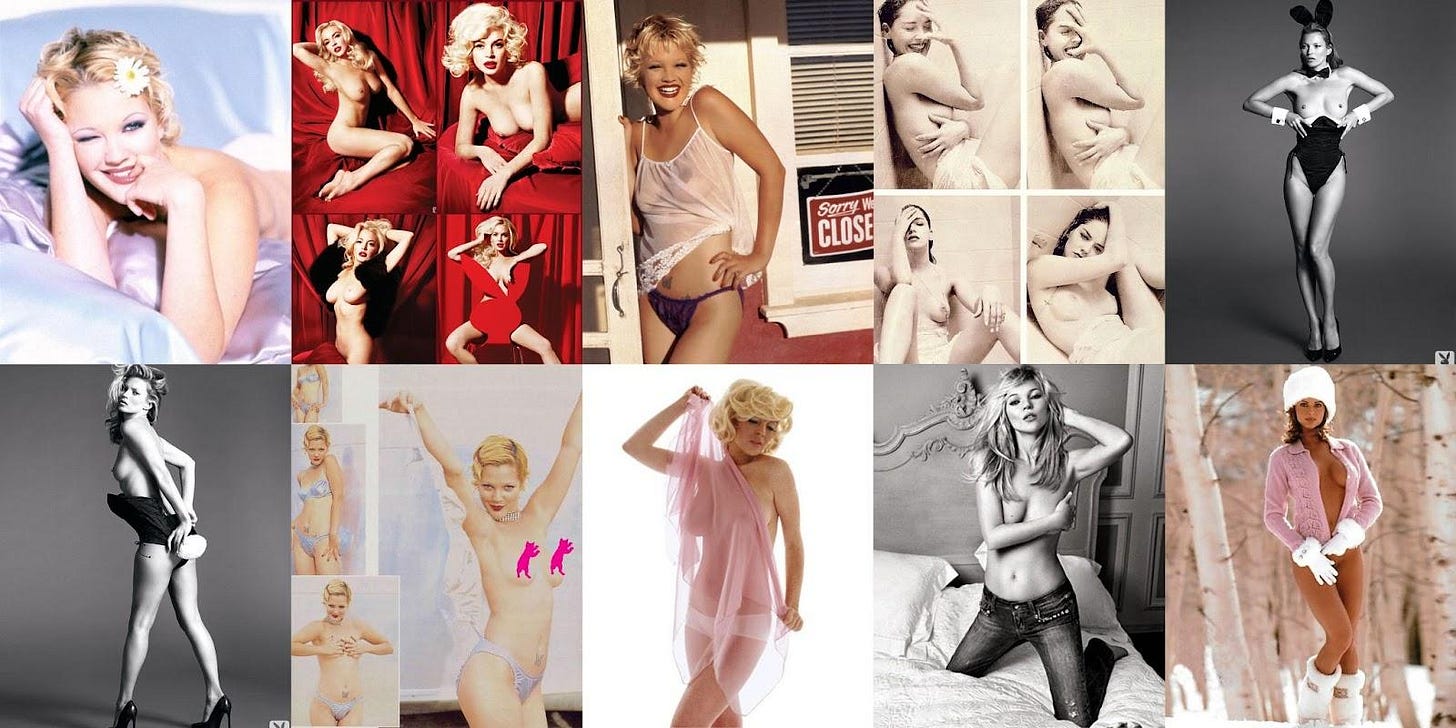

In reference to the nude, where we really see the audience come into play as a powerful force is in commercial photography, which has predominantly been produced for a male audience in magazines such as Playboy, featuring well-known models, actresses and celebrities posing nude, or semi-nude, to be shown in the magazine every month. This collection of photographs from various issues of Playboy (Fig. 6) displays an array of generic, stylised nude and semi-nude photographs. It is unmistakable from these examples that they are a display of the nude, not the naked. There is no hidden agenda; the models are sexually posed, not in a ‘moment’ but unnaturally in studio set scenes, and they are curated to show the women’s bodies solely for the pleasure of the audience. These nude images of women stop being art and become pornographic when they are put in the context of Playboy magazine, and by who consumes them. Photographic images for magazines like Playboy and other similar publications would not be a commodity without the audience as there would not be a demand for this genre of visual entertainment, consequently, the audience is the central reason why nude art and nude photography continue to be created and consumed. In Ways of Seeing, Berger introduces an interesting comparison between historic and traditional art patronage and the demand for modern commercial pornography. Berger discusses this idea of nude art and how this tradition in art history continues to live on, he says, ‘What is true is that the nude is always conventionalised.’ Historically, there was a demand for nude art as wealthy patrons commissioned nude paintings to display in their houses. Berger acknowledges this tradition and considers that the consumption of nude photographs in the modern world for viewer entertainment is merely just a reflection of art patronage in the past.

In the contemporary art world, mass consumption of images and art has increased the public’s exposure and view of art, therefore the audience has an increased role in regard to art. Nude art moved from paintings and sculptures by the great masters, to photography for commercial use and more often, male pleasure. In this photograph by Harley Weir from 2013-14 (Fig. 7), the viewer can see a semi-nude woman undressing, with her back facing the audience but she is looking directly at the viewer, acknowledging their presence. This could be perceived as an example of the naked. As with Degas Bathers, she is not posed provocatively, she is performing an ordinary, normal activity of removing her clothes, however, it is a contrived image of nakedness. It is staged and curated to appear a certain way, for it to appear as a candid shot photograph rather than a posed nude. Weir focuses on youth, fashion, and femininity, with the aim to challenge views on female sexuality and the idea of the female gaze, so one can assume her audience is predominantly young women who are interested in female empowerment, fashion or both, so although this piece may not inherently appear as sexual to its preferred audience, just the presence of a viewing audience looking at the posed, unclothed figure and the fact that it is a work of art, makes it the nude rather than the naked.

The artist's and image-maker's fascination with the nude coupled with the audience and its demands for ever more daring and boundary-exploring images has always been a dominant influence in the history of nude art. Without the patronage of the audience and the public enjoyment and support of this genre of work, the discourse on the naked and the nude would cease to exist. In analysing the significance and the weight of the public perception in regards to the paintings, drawings and photographs that have been discussed, it is clear that the existence and production of the nude in its many guises is double-edged and includes both the artist who creates the work and, more importantly, the audience who views the work. One cannot create an artwork that exhibits a naked figure without it representing the nude because art will always invite an audience, which inevitably transforms the naked into the nude.

Thank you for reading this essay! Stay tuned for essays and more from me. <3