The Silent Woman, Agency and The Male Gaze

Watching Vincent Gallo's "Buffalo '66" through the lens of the male gaze

The first time I watched Vincent Gallo’s 1998 film Buffalo ‘66, I was being introduced to the male gaze theory in my A-Level art history class. All the media I consumed from that moment on was viewed, read and looked at through the eyes of Laura Mulvey and her psychoanalytic analysis of the male gaze in cinema. In 1975, Mulvey coined the term ‘the male gaze’ in her essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Mulvey’s theory reveals that, in cinema, women can only view media from a secondary perspective, ergo, they can only see themselves as men see them. The viewer or surveyor (a man or a woman) steps into the shoes of a heterosexual man looking at a beautiful or desirable woman, so one is seeing the woman in an idealised, stylised and often unrealistic way; the way men have portrayed women. Mulvey suggests that the male gaze denies women a human identity because they are only seen as objects to be physically desired. When watching Buffalo ‘66, my first impression of Christina Ricci’s character, Layla, was her position as a product of the male gaze and a vessel to elevate the power of Vincent Gallo’s character, Billy. To explore this idea further, I will be using both Laura Mulvey's and John Berger’s writings to explore Ricci’s character and her role as a symbol of the male gaze in the film.

Buffalo ‘66 is Vincent Gallo’s dark comedy that follows Billy Brown (played by Gallo) who has just been released from prison for a crime he claims he was wrongly convicted of, and is forced to confront his troubled past. We see Billy as he navigates this day, eager to redeem himself to his dismissive parents. The film begins with Billy kidnapping a tap dancer named Layla who he forces to pose as his wife in front of his parents who don’t know he was in prison. This film is about Billy fighting his inner demons, confronting his dysfunctional past and his unconscious search for belonging and love. Throughout this, Billy and Layla form an unlikely bond, forcing Billy to be vulnerable and emotional. Buffalo ‘66 is striking and melancholic, an exploration of a man’s longing for redemption and security.

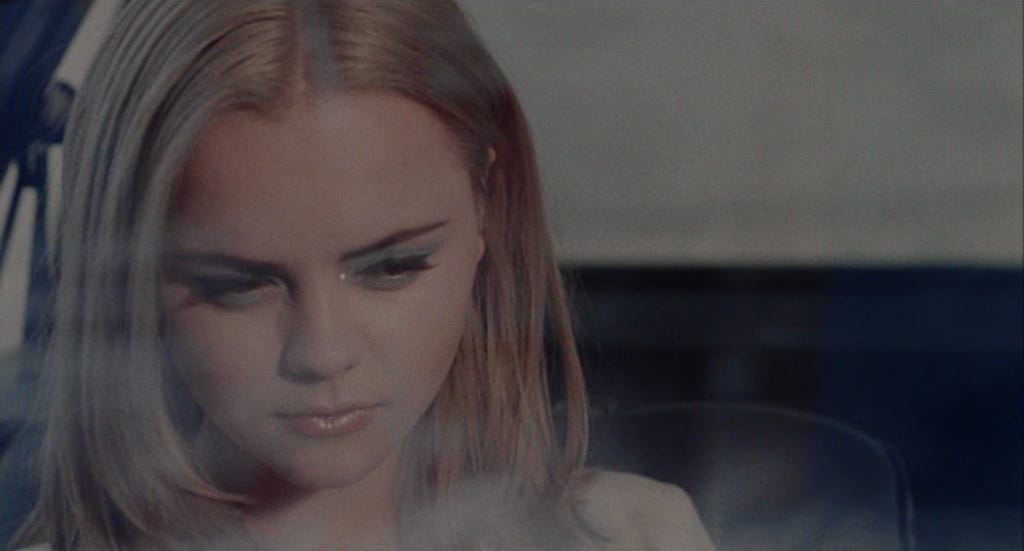

We first meet Layla mid lesson at a tap dance class where Billy is seen walking behind her. Layla’s age is ambiguous, she looks youthful in appearance yet is dressed maturely in revealing clothing. She is played by 17 year old Ricci but her character’s age is never mentioned, however it is evident that she is younger than Billy. Layla is dressed in a baby blue mini dress, blue fishnet tights and sparkly silver tap shoes. Her hair is platinum blonde with warm pink undertones, she has striking blue eyeshadow that accentuate her big round eyes, and blush pink pouty lips. She is the first ray of light we see in this film, it is almost quite jarring how vast the contrast between her and the rest of the film is, as the overall tone and colour pallette of the film is cold, grey and unsettling. This is to reflect the circumstances of Billy’s life at this point but when we are introduced to Layla, she is presented as a shining, angelic figure amongst the grey.

Layla is a woman with no agency, no power and no substance, we know nothing about her life before Billy or anything about her as a person apart from the fact that she tap dances. She is a poorly written female character with no development or individual character arch. She is what Mulvey calls a silent woman, or “the silent image of woman”. When Billy kidnaps Layla after her class she is frightened at first but her fear doesn't last long, she becomes very quickly agreeable and passive; under his spell, it would seem. Her undeniable and immediate trust in his character is indirectly asking the audience to follow along and see him as she does, as she is somewhat in awe of him. We, as viewers, can immediately trust Layla because she is harmless and innocent-looking, unlike Billy who needs this sweet and innocent woman to manipulate the audience's view of him. Layla’s purpose is to make Billy a more pleasant character, for the audience to see his potential, acknowledge his inevitable redemption and to care about him the same way she does. In an interview, Ricci says “She is his fantasy girl [...] she likes him no matter what.” almost suggesting that she is a figment of his ideal life, someone who sees him differently to the way the other women in the film see him (his mother and his ex-girlfriend). This idea of using a woman as a way to bolster the male character and as a way for a man to project his fantasies on an obeying female is implied when Mulvey states “Woman then stands in patriarchal culture as a signifier for the male other, bound by a symbolic order in which man can live out his fantasies and obsessions through linguistic command by imposing them on the silent image of woman still tied to her place as bearer, not maker, of meaning.” Layla is his ultimate fantasy, a woman who unconditionally adores him and does whatever he pleases.

Billy is initially presented as powerless; he has just been released from prison and has nothing but the clothes he is wearing. His power is introduced when Layla is introduced, echoing John Berger's statement in Ways of Seeing, 1972, that “A man’s presence is dependent upon the promise of power which he embodies.” The “promise of power” in this case manifests through Billy’s immediate control over Layla when he kidnaps her after her dance class. Berger continues, stating that “Her presence is manifest in her gestures, voice, opinions, expressions, clothes, charm, surroundings, taste...” suggesting that her role in the film, and in Billy’s life, is solely based on how she appears physically hence why her costume and overall look is so memorable; it defines her presence. Every aspect of her character - her appearance, costume, dialogue - serves to enhance Billy’s power over her. She speaks in passive and submissive tones, solely focused on him, expressing sentiments like “I really like you. I’m going to be really sad if you don’t come back.” and “I think you’re the sweetest guy in the world. And the most handsome.” It isn’t clear why she is saying any of this to him given how badly he treated her throughout the film. However, as stated earlier, her admiration for him serves as a significant tool of audience manipulation, asserting further Billy’s dominance, not only over Layla but also over the viewer. This additionally implies Layla’s lack of agency and her role as the silent woman which in turn, elevates Billy’s position and reduces her purely to a product of the male gaze.

Buffalo 66 offers a compelling exploration of the male gaze and how women are used as tools to elevate male power. The portrayal of Layla symbolises the male gaze through the writings of Laura Mulvey and John Berger. Layla’s role in the film serves as a vessel through which Billy’s power is enhanced; she is without agency or autonomy, a quintessential silent woman. Her presence in the film contributes to the elevation of Billy’s dominance, compelling the audience to perceive him in a more favourable light. Layla’s role as a passive woman epitomises the objectification of women in cinema, perpetuating the notion that women are purely objects of desire and pleasure. Viewing this film through the lens of Mulvey and Berger reveals the power dynamics presented in the film, allowing a critical reflection on the portrayal of Layla and her impact on the narrative. Overall, Buffalo ‘66 serves as a powerful example of how the male gaze continues to dominate cinema. Like Mulvey and Berger suggest, a woman’s role under the male gaze is passive, silent and powerless; made to be looked at.

Thank you for reading my essay! Share Fragmentary Girl with your friends. <3

<3