The Woman-Child in Wonderland

Exploring the Surrealist femme-enfant through Max Ernst and his infatuation with Alice (in Wonderland)

Throughout art history, the figure of the woman-child has taken on many forms, but one thing always remains: the woman-child is the ‘perfect woman’. The woman-child is typically defined as a woman with child-like qualities; pure and subservient, or a girl child with adult-like qualities; sexually precocious and ‘mature’. In art, this figure is most recognised for being passive, sweet and pure but the Surrealists transformed her. Their version was renamed the femme-enfant, she was curious and free with a wild imagination, with characters like Alice (in Wonderland) being an archetypal example of the Surrealist femme-enfant. In this essay, I will be discussing the characteristics and portrayal of the femme-enfant, referencing the importance of childhood in the First Manifesto of Surrealism, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and an early example of a woman-child figure in Surrealism. I will examine Max Ernst whose infatuation with the femme-enfant was manifested in his relationships with younger women, most notably Leonora Carrington, and how he envisioned them through the character of Alice. To Ernst and others in the Surrealist movement, Alice personified the Surrealist idea of the ideal woman; rebellious, enchanting and in touch with dreams and other realms. Ernst’s work throughout his career emphasises this desire; sexualising, exoticising and infantilising the women in his life who, to him, were not fully woman but child too.

Regressing to a state where you are your most curious, your imagination is flourishing and where you have no understanding of boundaries was essential to be in the Surrealist mindset. Andre Breton, one of the founding fathers of the movement, promotes this regression in the First Manifesto of Surrealism, stating that children “know no bounds”. The femme-enfant was conceived from this idea and her precursor, the femme-fatale. Instead of appearing innocent, pure and virginal like examples of the woman-child you might see in Pre-Raphaelite artworks, the femme-enfant was presented as rebellious, enchanting, mischievous and playful, breaking away from the Victorian idea that children are seen but not heard.

“This vision of the imperious girl child is presented as freer from herself, so rebelling against passive femininity, as traditionally defined.” - Morna Laing, Picturing The Woman-Child

A significant characteristic of the femme-enfant was that she is still a sexual being - hence deriving from the femme-fatale - the child-like nature of her is her appearance, mind and innocent curiosity. It was essential that she looked up to her male peers as mentors, for guidance and knowledge, a way to bolster male stature and position women as inferior. She couldn’t be completely naive however, she still had to contribute interesting ideas, and inspire creativity like a good muse should. A contemporary example of the femme-enfant was seen in the 2023 film Poor Things, with the character of Bella Baxter having the brain of a newborn baby but the body of a woman; perhaps the most literal woman-child ever created. Bella explores her sexuality with various men throughout the film who clearly gain a lot of pleasure from her lack of experience or knowledge in life and her dependance on them for guidance and intellectual enlightenment. As soon as she starts developing a rebellious intellect, independence and consciousness of the world around her - especially when she starts reading philosophy books - the men in her life no longer find her as desirable, as she is a threat to their hold over her. Although the women in the surrealist group were ‘accepted’ as artists in the movement, and evidently matched their male peers as highly intellectual writers, artists and creatives, the literature published such as the Manifesto (Breton, 1924), Nadja (Breton, 1928) and Arcane 17 (Breton, 1944) illustrate the lack of empathy or understanding they had for their female contemporaries. In the Manifesto, women do not even dream correctly, Breton claims they “disturb” the process and “tend to make it less severe” whereas “The mind of the man who dreams is fully satisfied by what happens to him.”1 No woman was ever presented as fully whole in their work, therefore the woman-child was the archetypal and accepted Surrealist woman.

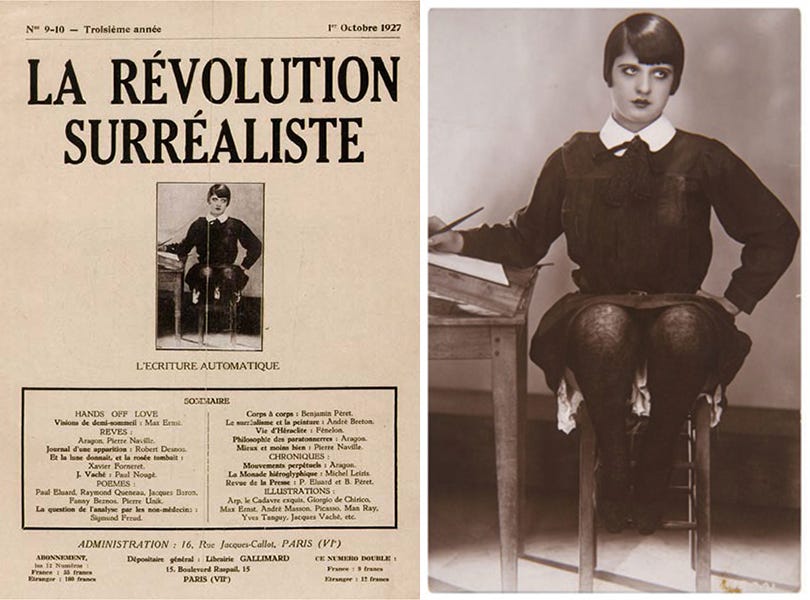

A photograph that I think perfectly encapsulates the vision of the Surrealist femme-enfant is by Albert Wyndham from 1927 which was on the cover of the Surrealist journal, La Révolution Surréaliste. The young woman is dressed in a school girl-esque outfit, a bow tied around her collar and the frill of her bloomers peeking out from underneath her skirt. Her facial features are round and youthful, her lips are small but plump, giving the viewer the impression that she is child-like and innocent. Despite her disapproving and cutting gaze to the right, her overall appearance is still infantilised. The rebellious woman-child is expressed through her pose, she is sitting on a stool not facing her desk, she is holding a pen to paper yet not looking at what she is doing. Her doe-like eyes focusing on something out of the frame suggests there is someone out of frame who she is disobeying, if she is a school girl then she is not doing her work nor is she sitting sensibly. She is the epitome of the child who acts out, not bound by rules. At the beginning of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, we are in the mind of Alice who is tired of her older sister reading her a book without any pictures in it. Her falling asleep and therefore rebelling against her duties of education is mirrored in this photograph of the naughty school girl. Alice was adopted by the Surrealists as a case study of the femme-enfant, along with the narrative of the story that used dreams and nonsense as a framework much like the First Manifesto of Surrealism.

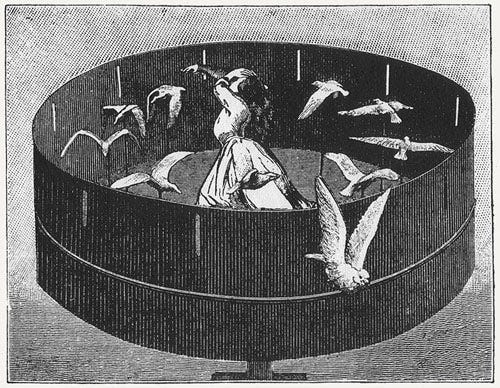

One artist who was deeply infatuated with Alice was Man Ernst. He was notorious for having relationships with women much younger than himself and projecting his desire for Alice onto all of them. When married to his 20 year old wife Marie-Berthe Aurenche, he projected her into his novel Reve d’une petite fille qui voulut entrer au Carmel (A Little Girl Dreams of Taking the Veil) as a little girl in similar garments to John Tenniel’s illustrations of Alice. The story recounts the dreams that a little girl has of being raped on her first communion. Dorothea Tanning’s translation of the book into English has since been adapted into an opera, and demonstrates the insidious and dark narrative created by Ernst “…at age seven and through the savagery of an ignoble individual she lost her virginity. It happened on the very day that first communion was refused her: she was too young, as her milk teeth proved. The individual, not content with having forced her, broke all her teeth with an incredible ferocity and by means of a large stone. Then she came back and said to the Reverend Father Denis Dulac Dessale, while showing him her bloody mouth:, ‘now I can take communion, I have no more milk teeth.’”2 The illustration to accompany this story, of the little girl being attacked by birds, is strongly reminiscent of Tenniel’s Alice in both illustration style and the appearance of the girl. The pose and scene is almost identical to Alice in a Shower of Cards. The story, both inspired by his young wife Aurenche and Alice, encapsulates the twisted exploitation of the image of girl children in the Surrealist movement and Ernst’s obsession with the woman-child as his ultimate muse.

In 1938, Ernst moved on to his next, much younger 20 year old lover, Leonora Carrington. His proclivity to associate his young partners with Alice was all the more prominent during his relationship with Carrington. Her likeness to Alice began at a young age, long before she met Ernst. She had rebelled against her father who detested her desires to be an artist, and after many years of disappointing her father at art school, she met Max Ernst and ran away with him to join the Surrealists. Ernst clearly saw her affinity to Alice as he painted two portraits of her entitled Alice (1939 and 1941). In his second portrait of Carrington, Alice in 1941, Ernst has reimagined Alice as a grown woman, although her body is almost entirely consumed by a bird feather garment, her breasts are revealed. This painting, to me, clearly represents Ernst’s sexual desire for Alice and though she is not visualised as a child, he is projecting a sexualised fantasy of a character who will always be immortalised as a child. It is a painting of his partner who he has a sexual relationship with but it is as much a painting of Alice, the child, who is the true object of his desires. This version of Alice is exoticised as a creature you may find in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, it is almost as if he has written an extension of her story that has tied her eternally to Wonderland and transformed her into a creature or character you might meet when you are there. It could be interpreted that Ernst has imagined himself in the story; he arrives in Wonderland and happens upon Alice, this beautiful and strange bird-like creature. Perhaps he sees himself as her guardian, portraying her as a bird as if to grant her freedom; the apparent freedom that is essential to the femme-enfant’s nature. The first Alice portrait he did in 1939 is a more abstract version of his Woman-Alice. She is still a bird-like hybrid yet she appears to be protruding out of her feathered disguise, revealing more skin. It seems as if she isn’t the bird but has instead been engulfed by the bird whose head we can see above - the large beak pointing down at - her exposed vulva, framed in an oval of green feathers. This portrait is more erotic than Alice in 1941, drawing attention to her sexuality and highlighting that she is now a woman. By aging Alice and presenting her as a sexual being, Ernst is imagining a context in which his desire for Alice is accepted.

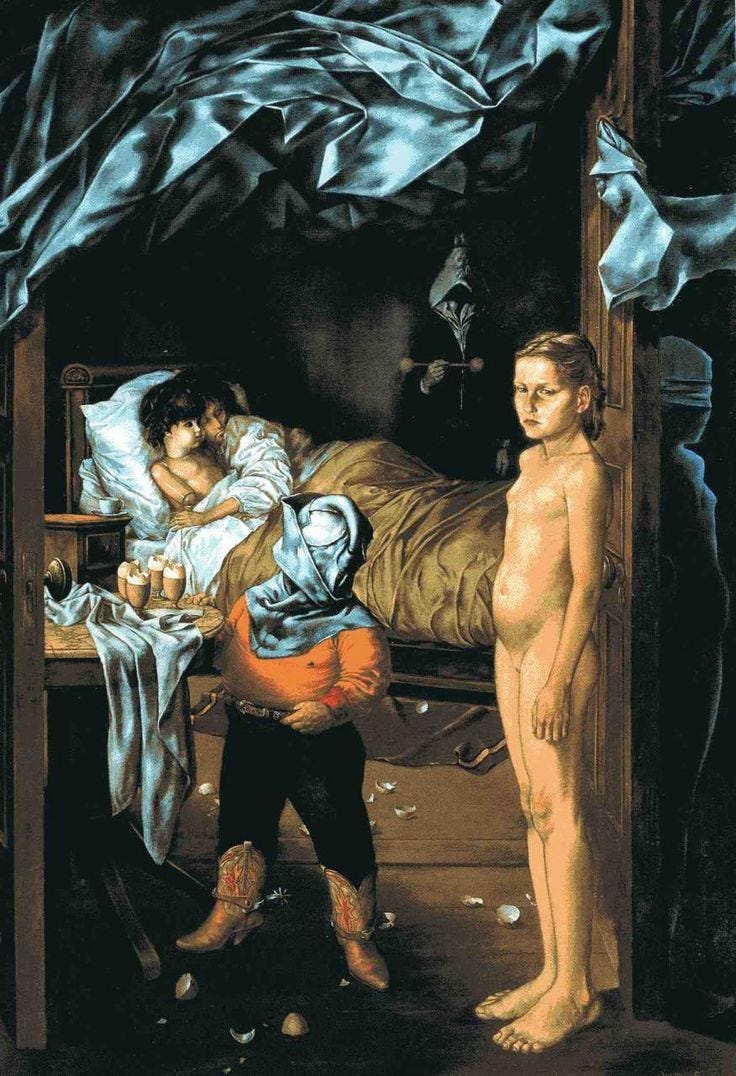

Max Ernst’s fixation with envisioning his partners as the femme-enfant didn’t stop with his last wife Dorothea Tanning who was 30 when they got married. Although she was no longer on the cusp of childhood, she was still significantly younger than him and therefore another vision of the femme-enfant or Alice. Tanning’s work explores the horrors and surreality of childhood, often depicting young girls in frightening and uncomfortable scenes. Her 1943 painting Eine Kleine Nachtmusik depicts two Alice-like girls in the hallway of a hotel, one standing before a giant, almost monstrous sunflower and the other leaning lifelessly against a door frame, with implications that she is a doll. Tanning’s exploration of the woman-child is often perceived as a critique of the idea that the perfect woman was child-like and a rejection of the Surrealist ideals. Her depictions of young girls appear far less sexualised as Tanning often drew from her own experience growing up, with the exception of The Guest Room, 1950-52. In this painting, the prepubescent girl is nude in the doorway of a dark room. It is supposedly about the erotic imagination of a young girl, the nightmarish scene around her depicting the figure of death looming over the bed of another young girl who grips onto her disfigured doll, and a small gremlin-like creature in cowboy boots staring at the naked girl despite not having a face. It is Tanning’s most uncomfortable painting to view, and lends itself to Ernst’s early versions of the woman-child in his novel A Little Girl Dreams of Taking the Veil, again representing a young girl’s apparent sexual fantasies.

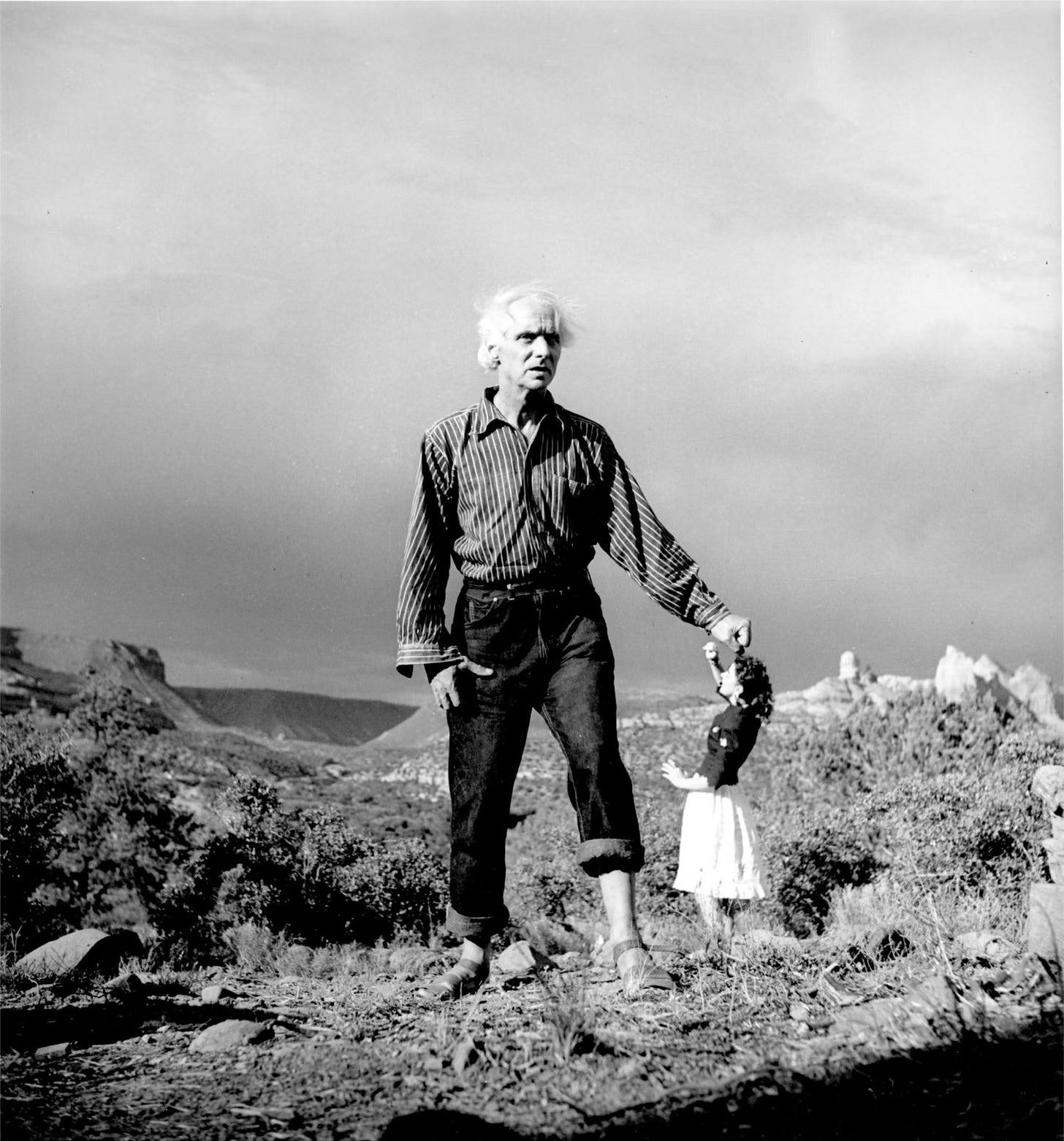

In 1946, Lee Miller photographed Max Ernst and Dorothea Tanning in Arizona. This black and white photograph is a double portrait collage, depicting a giant Ernst and a tiny Tanning. The Giant Ernst is gripping onto Tiny Tanning’s hair as if she were a doll. Her pose and dress seem to so perfectly mimic Tenniel’s illustration from earlier, Alice in a Shower of Cards, contrasting with Ernst’s casual clothing and powerful stride. It is as if Miller has reimagined Tanning as one of the girls in her paintings, transforming her into the woman-child, doll-like and overpowered by Ernst. This photograph also mirrors Carroll’s story, Alice grows and shrinks throughout her time in Wonderland, being her most powerless and vulnerable when small. This Tenniel illustration of Alice and Humpty Dumpty also mirrors Miller’s photograph, Alice looking up at Humpty Dumpty whose scolding facial expression mimics Ernst’s and whose large hand looms over Alice. Although this photograph isn’t by Ernst, it still asserts Ernst’s infatuation with Alice and viewing his partners in the light of the femme-enfant, as well as visualising how Ernst views himself.

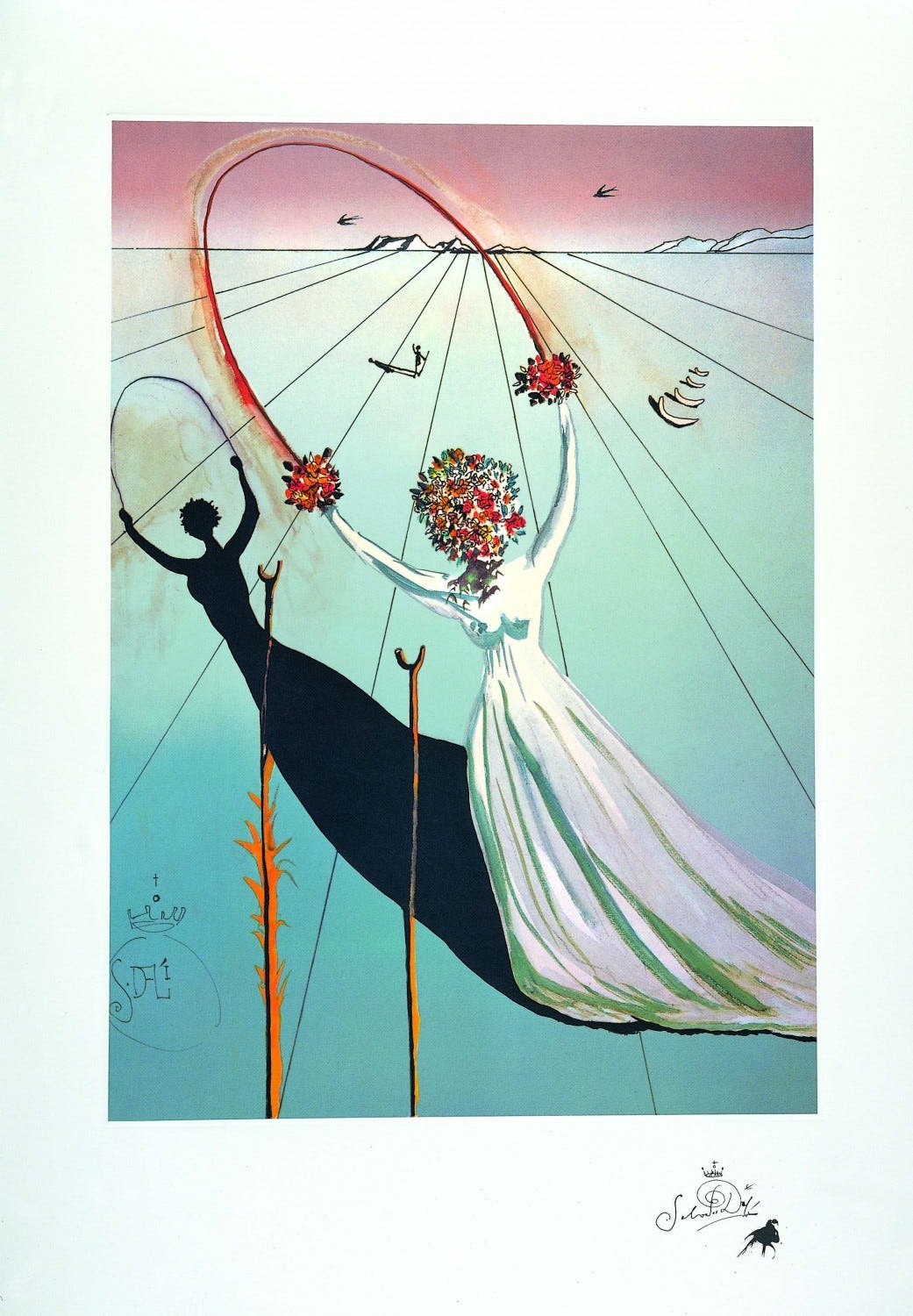

By transforming the woman-child, through their obsession with childhood imagination and curiosity, the Surrealist’s curated an ideal woman; the femme-enfant. Alice became the vision through which all interpretations of the femme-enfant mirrored, she characterised all the essential qualities of Surrealism. Max Ernst, in his various relationships with younger women, projected each of them as an Alice-like figure, notably in his erotic novel, his Alice portraits of Carrington and in Tanning’s work. His reimaginations of Alice projected her into sexualised scenes of rape fantasies and womanhood as well as enhancing the power dynamic of Ernst and his partners. Although my focus throughout was Ernst’s infatuation with the character, Salvador Dali, in his illustrated version of the book, envisioned Alice with a woman’s body and prominent breasts beneath her white gown. His Alice is also holding a skipping rope in every illustration, reflecting the femme-enfant. Surrealism’s fascination with Alice was more than just an admiration for her imagination, curiosity and charming personality, there was a stronger, sexual attraction towards her which is reflected in their work exploring the figure of the femme-enfant.

Thank you so much for reading! This essay was a lot of fun for me to research and write, I got to combine a few of my favourite things: feminism, my deep anger at Surrealist men and Alice…

Bibliography:

Andre Breton, First Manifesto of Surrealism, 1924

Catriona McAra, Surrealism’s Curiosity: Lewis Carroll and the Femme-Enfant, 2011

Lewis Carrol, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, 1865

Max Ernst, A Little Girl Dreams of Taking the Veil (Reve d’une petite fille qui voulut entrer au Carmel), 1930

Morna Laing, Picturing The Woman-Child, 2015

Robert Phillips, Aspects of Alice: Lewis Carroll’s Dreamchild as seen through the Critics’ Looking-Glasses, 1971

Andre Breton, First Manifesto of Surrealism, 1924 (p.13)

So fascinating to read, brilliant as always!

That was so interesting to read and beautifully written