“Men have always had privileged access to the sight of the female body.”, this quote from Rosemary Betterton encapsulates the true nature of voyeurism. It is not just about pleasure in looking, it is the pleasure in the privilege that men have to look at a nude woman. We can all see a nude woman whenever we like, it is not exactly forbidden; on the internet, advertisements, on the street, TV, in art galleries, film and even in a hotel lobby. In this essay, I will be discussing voyeurism in relation to the infamous art installation The Box (1999), examining it through the lens of Freud’s scopophilia and Laura Mulvey’s later readings on scopophilia in cinema and visual media. I will be considering the power The Box has in reducing women’s agency and desensitising people from seeing what is typically private. I will also be discussing pleasure in being looked at and why this idea could be an illusion when it comes to The Box.

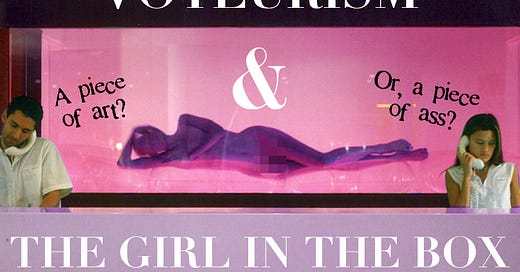

In 1999, The Standard Hotel in Hollywood opened an ‘art’ installation in the lobby. You might expect this to be an abstract sculpture, maybe a water feature, something you would normally find in the entrance of a hotel. Not in The Standard. The ‘art’ installation was called The Box which was essentially a human fish tank that sat behind the reception desk, on display for all visitors. Inside this box were human models, commonly known as Box Girls, who were posed - sometimes nude for special occasions but usually in white vests and boxer shorts - doing whatever they wanted in the box. They could read, write, watch TV, even sleep; anything as long as they were not making eye contact with hotel visitors. These women (and occasionally, but rarely, men) were hired to do weekly shifts in this 15 feet long box. The Box was created by Shawn Hausman, an ultra-modern, cinematic-esque designer who began his career in film as a production designer. Hausman is most recognised for his hotel interior design that incorporated pop culture and narrative, including work for the Chateau Marmont, and all The Standard Hotels.

Voyeurism and scopophilia play a significant part in The Box as an installation, transforming these women, via the display, into objects of desire only to be looked at, an almost forbidden and desired thing; therefore exoticising and objectifying them. In Three Essays on Sexuality, Freud coins the term scopophilia as a way of describing the sexual satisfaction a voyeur gains from looking, often looking at something erotic or arousing, something perhaps one should not be looking at. Freud associated scopophilia with transforming another into an object, subjecting them to a powerful gaze. The Box itself is not a forbidden thing but the models are, “you can look but you can't touch” and according to Freud “Visual impressions remain the most frequent pathway along which libidinal excitation is aroused.” Looking is perhaps the strongest sexual tool.

The Box itself is powerful, it represents patriarchal control over the female body. Not only did a man create it, but men are predominantly on the other side of it, or at least the ones that engage the most in the installation. The female body is so visually accessible, the fact that you could stay in a hotel in Hollywood and watch a semi-nude woman doing nothing for hours highlights the privilege men continuously have over the sight of women's bodies.1 The actor Vinny Argiro, a regular at The Standard Hotel said “It’s nice to watch girls sleep. Sometimes I prefer that. I like girls best when they're asleep.”2 His response accentuates the joy men feel over seeing women in powerless positions, devoid of agency and reflects the pleasure men gain in having the freedom to look at them in uncompromised positions. This also links to what Betterton argues in Looking On, “Male spectator's employment is not solely erotic. It is also connected to a sense of control over the image. The woman’s body is posed and framed for him, while his own body remains doubly hidden.” This dynamic of control and the unconscious power these men may feel over seeing a woman in little clothing in a tight, confined space accentuates the voyeuristic nature of this ‘installation’. It is not exclusively about the gaze but also about the cultural control men have in forming how women’s bodies are seen and presented.

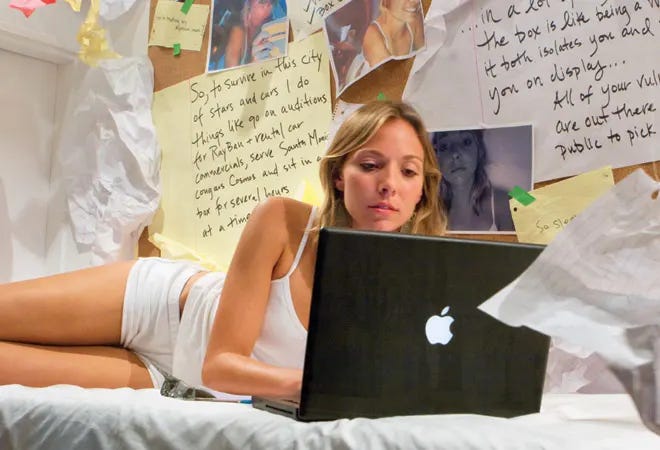

Lilibet Snellings, a Box Girl and writer, spent her weekly shifts in The Box writing a book about her experience. Despite enjoying her time as a Box Girl, she writes about the darker aspect about being in The Box. She said “By far the most horrifying thing was when a man thought it was like the Red Light District in Amsterdam, so he thought he could rent me and take me up to his hotel room.”3 This again connects back to Betterton discussing the sense of power men feel over the vision of a woman’s body. The Red Light District in Amsterdam is a prime spot for prostitution, strip clubs, peep shows and other various nightlife activities. What it is famous for is window prostitution where sex workers are illuminated by red lights and perform behind glass to lure in potential clients from the streets. The Box strongly mirrors this experience, the women behind the glass may not be overtly performing sexually, but it is the symbolism, the unconscious connection between window prostitution and The Box that one cannot seem to ignore. This is what I call Male Symbolism, which I will define as the unconscious associations men make when a woman is wearing or performing something associated with sexual connotations (red lipstick, fish nets, laying half-naked in a glass box). Due to the prevalence and existence of these symbols, men assume that the woman is exuding a certain sexual energy which ultimately influences the way he views or treats her (staring at her, calling her derogatory names, assaulting her, asking if she's for rent etc.) As John Berger states “Men survey women before treating them. Consequently how a woman appears to a man can determine how she will be treated.” The women in The Box can be easily mistaken for window prostitution, it is a likely comparison, and therefore men will treat these women accordingly. They see the Box Girls as objects, property, something to be looked at, and in some cases, something to be rented for pleasure.

Snellings questioned whether she was “a piece of art, or a piece of ass?” yet concluded she was probably both. Voyeurism in art is significantly different to voyeurism in real life. In real life, voyeurism is a solely sexual exploit and is a violation of the Sexual Offences Act. In art, you are essentially given permission to be a voyeur, whether the subject knows it or not. This begs the question, how do we define The Box? It is called an art installation but it is solely reliant on real people being looked at by the public in a typically private or vulnerable position. I would argue that The Box invites real life voyeurism not artistic voyeurism. Visitors of the hotel would not necessarily recognise the box as art, such as the man who thought it was like window prostitution and the actor who just liked watching the girls sleep; neither made any connection to it being art. It isn't discussed, critiqued or appreciated as a piece of art, it is viewed as a novelty, a way to look at women and gain pleasure from looking at them. If The Box was seen as art, the response would be significantly different. People would discuss The Box as an art work rather than exclusively talking about the women inside The Box, and Snellings wouldn't be questioning whether she was “a piece of art, or a piece of ass”.

When compared to Tilda Swinton’s installation The Maybe, we can see notable contrasts. Swinton’s piece was viewed as art. It was displayed in a museum setting, it was exclusive to museum visitors and it had meaning and intention. The Maybe was consciously art, it was displayed alongside other objects and artworks that expressed the concept of time passing. Another important contrast between The Box and The Maybe is that Swinton was not at all performing sexually, she was fully dressed in oversized casual clothing and she was asleep in normal sleeping positions. She may have been performing to an audience of museum visitors but she was performing a human representation of the passing of time. There is a difference in subjecting yourself to the gaze of a voyeur as opposed to someone doing it for you.

We have pleasure in looking but what about pleasure in being looked at? Snellings mused on feeling more like a voyeur herself in The Box, enjoying both being watched and watching the people watching her; “both the observed and the observer.” This idea of reverse scopophilia is briefly brushed upon in Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Is pleasure in being looked at really a reality or simply an illusion? The Box alludes to the idea of “you can look but you can't touch”, creating the fantasy that these women in The Box are in control of the gaze because they are consenting to it and viewing it for themselves. This, however, poses the question of who is actually in control? I would argue that the models in the box don’t have any power over how they are presented or viewed once inside the box. Instead, this illusion that they enjoy the gaze or feel in control of the gaze links to Berger’s idea of the internal male gaze: “The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female. Thus she turns herself into an object - and most particularly an object of vision: a sight.” The idea that they are in control or are themselves the voyeur is impossible when what is behind and in front of The Box is men, and the pleasure they are gaining from being looked at is the internal male gaze. So, sure, the Box Girls can say they enjoy watching the visitors of The Standard Hotel and mean it but that doesn't mean they have the ultimate power when the internal male gaze comes into the equation. Perhaps this is so obvious, which is why Mulvey did not really elaborate on the idea of pleasure in being looked at in her essay!

Voyeurism is an essential part of the discussion and discourse around The Box. The fundamental understanding of this art installation is that a woman sits behind glass and anyone who steps foot in the hotel can look at her, talk about her and make judgments about her. The Box in this sense acts as a powerful tool over the gaze and represents male dominance over the female body. As Betterton said, seeing the nude female body is a privilege that all men think they have which is demonstrated by visitors of The Box who mistook it for window prostitution and asked if the model was for rent. This connection represents how men will treat a woman according to her actions or dress if either can be at all connected to sex.

When comparing voyeurism to voyeuristic art, it is hard to accept The Box as a work of art as it relies solely on public voyeurism. Swinton’s The Maybe, on the other hand, didn’t necessarily invite a voyeuristic audience despite it being an almost identical visual concept. Both artworks expressed such different meanings and perceptions, both inviting a gaze but not at all the same kind of gaze.

Despite being gazed upon for 7 hours a day, some of the Box Girls claimed to enjoy this part of the job. This raises questions about whether there is pleasure in being looked at. When thinking about the connection between the gaze (voyeurism) and patriarchal power, it suggests that pleasure in being looked at is an illusion and could in turn be linked to an internal male voyeur within, as Berger stated.

The Box, overall, serves as a powerful visual example of voyeurism and the power of the male gaze. With a number of pop culture cameos in shows such as Sex and the City, The Box is nothing more than an objectifying gimmick subjecting the enclosed women to an endless gaze.

Thank you so much for reading this essay!

This topic was originally going to be a short case study on The Box but whilst researching for a different essay on voyeurism, The Box kept haunting me. The more I researched the more I was grateful that this hotel closed down!!

Bibliography:

Sigmund Freud, Three Essays on Sexuality, 1905

Laura Mulvey, Visual and Other Pleasures, 1989

John Berger, Ways of Seeing, 1972

Rosemary Betterton, Looking On: Images of Femininity in the Visual Arts and Media, 1987

Lilibet Snellings, Box Girl: My Part-Time Job as an Art Installation, 2014

Lilibet Snellings, “Box Girl” Pays Tribute to Shuttered Standard Hotel, 2021

Elisabeth Schellekens, Taking a Moral Perspective: On Voyeurism in Art, 2012

Maria Elena Fernandez, Girl-In-The-Box Display Is a Think Tank of Sorts, 2001

Jocelyn Silver, Inside a Glass Case of Emotion: Meet the Standard’s ‘Box Girls’, 2018

Rosemary Betterton, Looking On: Images of Femininity in the Visual Arts and Media, 1987

Lilibet Snellings, Box Girl: My Part-Time Job as an Art Installation, 2014

a thought-provoking read and well written as always!

Woah to the part about internal voyeurs. Beautiful way to engage with your audience. I definitely see the trope of the box reflected back in music and fashion as well!